Recently, I’ve encountered several types of mushrooms and fungi. A beautiful design language, always with a roof! The stems, a rounded pear shape or as slender as a matchstick. The caps resemble Cyrano’s nose, or are as fragile as the curved skirt of a classical dancer.

Architecture in sculpture

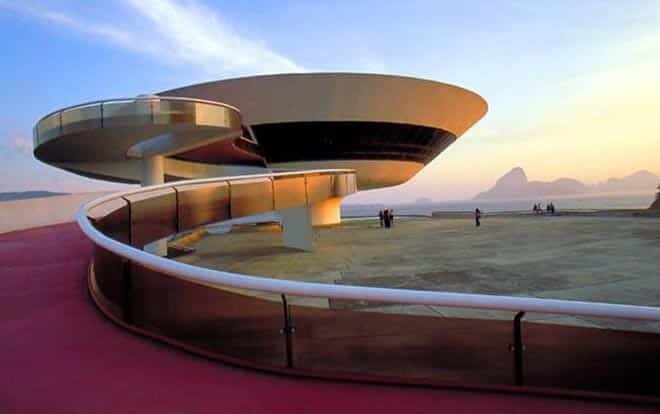

The captivating, multifaceted shapes of mushrooms and fungi can be found in appealing architecture. There are directly identifiable examples, such as the church of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp by the architect Le Corbusier. The church has organic shapes, not immediately identifiable as related, but palpable as a mystical power, something I can also experience when a mushroom or fungus surprises me. The Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, designed by Oscar Niemeyer, has a distinct mushroom shape. Rem Koolhaas, while walking in the woods, once looked up and saw the penthouse of the Byzantium (Amsterdam) clinging to a trunk.

Nôtre Dame du Haute Ronchamp le Corbusier

Museum of modern Art Rio de Janiero Oscar Niemeyer

Byzantium Amsterdam Rem Koolhaas

Surprising symbiosis

You find mushrooms and fungi by chance; it’s surprising and fascinating. They can suddenly appear. Yesterday you were walking here too, and then there was nothing, and now! A single one at the foot of an alder tree, or a whole circle around it; the fairy ring. Above ground, loosely scattered specimens in a circle, connected underground by an ingenious network of threads (mycelium).

What they delight in is decomposing, rotting, breaking down. Sometimes fresh-smelling air, sometimes damp and musty. Yet this group of organisms possesses everything that makes them fascinating to use. You can’t plant them, but you can create the conditions so that the diverse fruiting bodies suddenly appear as a surprise. On thinner and thicker stems, stacked or loose, in the shade, where it’s already damp in early autumn, after a year, some pioneers, mainly fungi, will appear. After that, things move quickly, insects join in, and gradually you’ll see a whole landscape of fungi emerge. If your garden is larger and you can create a small forest, the mushrooms will quickly follow, spreading a lot of fallen leaves each year. Another (few) years later, more divers mushrooms will appear, living in symbiosis with the tree roots.

One November day in 2018, I visited a park in Berlin. In a remote corner, I found a landscaped area with a section primarily containing mushrooms, fungi, ferns, moss, and water. Various hard and soft woods were piled together under trees, sometimes with a structure similar to that of your own firebox, and sometimes like branches tumbling over each other. Beside and among the thick green carpets of ferns and moss stood and sat a variety of mushrooms and fungi, sometimes clustered together, sometimes as single specimens. White, gray, red with white speckles, chestnut brown, orange, yellow—a vibrant diversity. This was stimulated by drier and wetter areas, by young and old, decaying wood, by the hard species of Acacia, Oak, and Sweet Chestnut, and by the softer species of Willow, Beech, and Lime. Damp scents, only streaks of light through a filtering green- and brown-tinted canopy, and the main and supporting players who had carved out a niche through their mycelium. It was a special atmosphere that rarely occurs, so I resolved to apply the conditions for fungi and mushrooms in my projects when appropriate. Looking back, I’ve done far too little so far, so soon…