Folly

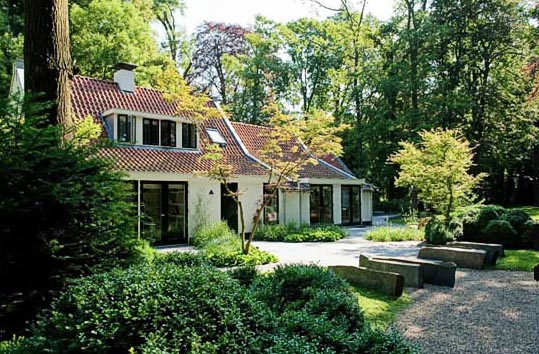

In the winter, the trees are bare and you experience the hard lines of the houses and buildings in the street and on the square. Those hard blocks have now been softened by light-filtering trees. We have now become largely accustomed to all the leaves once again, the fresh scents, the active birds, frogs, butterflies and beetles, and we are once again surprised, just like every year, about the variation of colours of the greenery and flowers. Whether it be a small garden or a large station square, all the stone mass revives in combination with greenery; from ground-cover plants to the broad outgrowing Chestnut tree. In green cities and villages, and larger and smaller gardens, it is precisely this match between stone mass and greenery that is often well understood.

Wood or stone with a design function, such as a pergola, a low wall or ‘a collection of objects’, also calls for an interplay with the greenery; reinforcing each other. It is different for a monumental artwork: a suitable spot is sought in a park, for example, as exhibition space.

In the case of a garden object, such as a pergola, it is about a structure that forms a unity with the characteristics of the designed greenery; there is a connection. As a result of this, the artwork changes with the seasons, the ageing, and is not complete without that interplay with that greenery.

In Ireland, a recognisable image like this axe brought a smile to my lips; a very special connection with the location….

Something that has fascinated me for years, in terms of the combination of stone mass and greenery, is the folly. The term is used worldwide and, as the word would suggest, is an English invention, although I am convinced that the Romans were also acquainted with this phenomenon, given their way of life and flair for architecture and art. The most common meaning of the word folly in English is foolishness, the meaning in this case, however, is; ‘a joke in the landscape’ or ‘a building that fools you’, Wikipedia calls it: ‘a non-conventional building, unsuitable for accommodation or other functions, and serving no other purpose than decoration.

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716-1783) was, as far as I am concerned, the inventor of the folly. As a result of his father’s network, his star rose quickly among the aristocratic nobility. He is the inventor of the English landscape style, as a reaction to the formal/ordered Renaissance style. Whereas this Renaissance style (take, for example, the gardens of Versailles of Louis IV, designed by André le Notre) continues endlessly with symmetry on both sides of the designed axis from the home/building, the English Landscape style soon abandons this and flows in wavy lines delineated by a simple grass or gravel path accompanied by trees and green plains of grassland, which subsequently merge into woodland and nature. His style gained many followers over the world and was also applied in our small country; country estates but also, among other things, gardens on the river Vecht were constructed in this style.

Capability (nickname) designed follies in many gardens, such as in the Stowe Gardens in Buckinghamshire, where he was head gardener; where there are no less than 40 examples. The first time that I heard of the folly was in the story of Wimpole Hall. The ‘problem’ was that the English country estates from that time were so vast that you could no longer gauge the length and width. If you were then standing on your terrace with a companion and a refreshment in your hand, it was slightly disappointing. Capability devised a spot at Wimpole Hall for a mock ruin; a strategic place on the hill, as a result of which the landowner could smile once again.

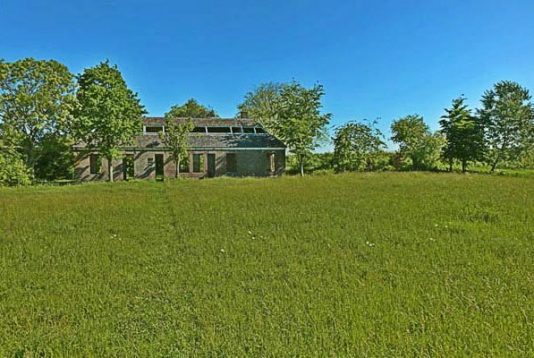

Follies are not, therefore, haphazardly placed objects. The objects make the place together with the greenery. It is a place that strives to appear as if it has always been that way. The positioning of the folly has a well-though-out purpose. Looking at it from the house, the landscape, and walking towards and past it, you connect with that spot. The folly; dominant, the eye-catcher, standing or lying in a landscape of grass, meadow, hedges and streams. The folly can also be that place where you want to go to; a small, attractive ‘garden temple’ partially surrounded by trees and shrubs.

The term folly has received a slightly broader interpretation over the centuries, not so strange considering it seems to be an umbrella term, but in spite of the fact that the small buildings are beautifully conceived and executed, it seems somewhat strange to me. The bus stop in Groningen by Rem Koolhaas and the lookout tower of Zaha Hadid are called follies, for example, but is that actually the case…

Something that did pleasantly surprise me was a graduation project from the TU Eindhoven/Eindhoven University of Technology (Urbanism and Urban Architecture) by Steffie de Gaetano ‘Follies as memory of the Arnhem brick industry’. She depicts the brick industry, which is slowly disappearing here. The aim here is to explore the surroundings, the nature conservation area around the follies, and to become aware of this history.

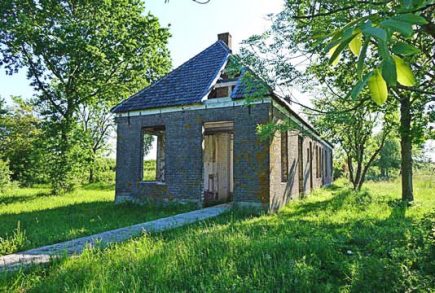

Approximately 5 years ago, the Society for the Preservation of Nature in the Netherlands (Vereniging Natuurmonumenten) invited me to contribute ideas about a vacant building ‘de Karantijn’ from 1880 in the Oude Polder at Tiengemeten, the oldest part of the island.

After people first cultivated and grew here before the 18th century, the Oude Polder (Old Polder) was designated as a quarantine area around 1805. This area on the island in the Haringvliet inlet, which was lockable as a result of an existing dike that could be patrolled, was very well suited as gateway for the trading ships returning from Asia. The ship had to be anchored and the crew was examined by a barber/surgeon, ‘dressed in linen soaked in vinegar’, in order to diagnose diseases like the plague. Next to the wooden barracks for these patients, there was a farm in this quarantine area, which provided all the food and accommodation for guards. Around 1875, the island stopped functioning as a quarantine area and the government established an oil, munition and powder store there. De Karantijn was built; an elongated sleeping accommodation and residence for guards, staff, loaders and unloaders. It later received the function of Volkskeet or a ‘shed/hut to accommodate workers’. From the 1970s, it was put into use as 3 holiday homes. The Society for the Preservation of Nature in the Netherlands became the owner of the island in 1994 and had to come up with a new plan due to the state of the building, which had become uninhabitable. A cost estimate for restoration was rejected. Demolishing it was not an option, as there was so little left of the history on this piece of island, but what does one do with such an object?

As a result of my explanation and references (which included Capability of course) the organisation fell for the phenomenon of a ‘folly’: looking at it from the landscape, and walking towards and past it, you connect with this spot. The building is linked to the turbulent history of the Oude Polder by a concrete path; the thick clay, which has heard and seen everything over the centuries. The openness that the folly now has, no windows, no doors, a ripped-out roof symbolises open space, freedom, no restrictions in contrast with the past. The nature sets to work inside, around and with the building, a synergy, reinforcing each other.

The Society for the Preservation of Nature in the Netherlands is going to start using this place as a meeting place for, among other things, music, theatre, literature… the plans are beginning to take shape.

Tip: Take a look also at http://www.dekunsten.net/dk-trips-hombroich.html open-air museum. Lots of beautiful things to see with several buildings by Erwin Eerich, sculptures in the landscape, folly?

and Spomenik, landscape objects, spectacular; Yugoslavia’s historic futuristic creations of abandoned abstract WWII monuments, sculptures and memorials from 1960-1990.